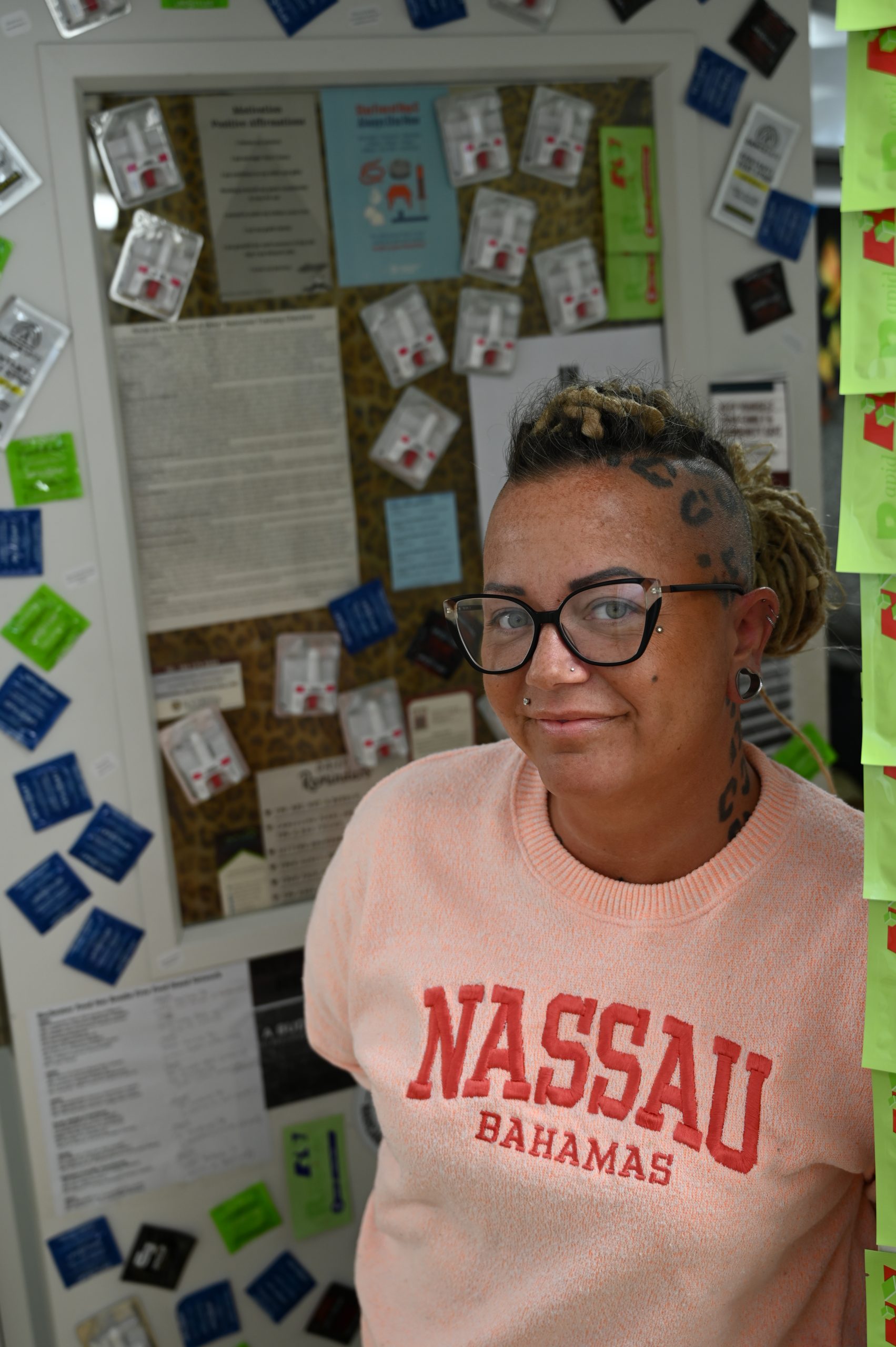

Stephanie

Going Back to Give Back

When a new resident arrives at Person Centered Housing Options’ Flower City Apartments, they meet Peer Advocate Stephanie Forrester. Stepping into her office, they pass through a door covered with taped-on Narcan boxes, condoms, and fentanyl and xylazine test strips. On her desk she keeps a large jar filled with candy and sticks of lip balm. Next, Stephanie hands them their move-in kit (a garbage can, kitchenware, cleaning tools) and lets them know when they can access food pantries, R-Community Bikes, and other partner resources to help smooth their transitions. These are just the first steps Stephanie takes to open the conversation with each resident on the way to building trust.

Stephanie knows that each person has decided to start over at PCHO, and she stands ready to support how they choose to approach their recovery. It is how she would want to be supported.

“I’ve been on the side of being unhoused, being in active addiction, practicing harm reduction, sex work, navigating court to get custody of my kids back – I’ve been through it all,” she said. For years she and her husband Justin were ever trying to get sober, together.

It was during that time of her life that she first connected on Facebook with PCHO co-founder Nick Coulter. Years later, well into her recovery, Stephanie would see a post about openings at PCHO and apply. Her own lived experience and subsequent years of work in the peer advocacy space made her an ideal fit.

Stephanie traces the turning point of her life to October 2016, after a stay at Loyola Recovery Foundation, a detox and inpatient program in Hornell, New York. Earlier that year she and Justin lost custody of their children to her father. When she successfully completed the program, the first night out she spent sleeping in the basement of her old apartment building. The next day a friend living in Bergen

Stephanie

picked her up and she began the long process of finding boundaries, knowing her worth, and choosing how to maintain her recovery. It was a time of navigating many complicated systems – DSS appointments, housing applications, and regaining her drivers’ license.

Then in January 2017, 100 days into her recovery, Justin died of an overdose.

It was the first loss Stephanie had experienced sober and the temptation to use to numb that pain was intense. But she knew she would not recover if she used again.

It is having walked this path that Stephanie can forge the connections she has with her residents. She estimates that 40% of the people she serves as a Peer Advocate are people she knew while living in active addiction and unhoused herself. She starts by showing each one that they are valued and loved, and then by being there for as much guidance as they want in navigating those complex systems.

“I learned a lot about boundaries and understanding my worth. Just because I am someone with a substance use disorder and who has been living this lifestyle, doesn’t negate the fact I am human and worthy of being respected,” she said.

As a Peer Advocate, she acts as a kind of ‘house mother’ who helps people recognize the building as a safe, supportive environment. She also, along with other Peer Advocates who work for PCHO, is available to accompany residents on the appointments for the services they need to rebuild their lives, acting as an advocate, a friend who stands by in the waiting room, or simply as a ride.

The community-building she models has caught on. Living at Flower City Apartments can be a healing experience. It’s where people feel safe enough to begin unlearning survival behaviors, start making healthy connections, and unpack how to protect their peace and their space.

Stephanie often reflects on how her life has come full circle. She regained custody of her children and bought her own home on the east side of Rochester. Working as a Peer Advocate in the Flower City Apartments is bittersweet. A decade prior, before PCHO acquired and rehabilitated the units, the condemned buildings were a location known for criminal activity and drug use — and Stephanie herself used here.

Today she finds her peace in being of service to others. In the residents who are here to start sewing up the gaping hole in their life, wherever it came from. Her happiness is in being one of those strings.